The Silent Failure Mode in Lunar Foundations: Differential Settlement Driven by OCR Contrast*

- Roberto Moraes

- 5 days ago

- 12 min read

Introduction

As lunar surface infrastructure transitions from conceptual studies to engineered systems, a critical failure mode remains largely unaddressed: differential settlement driven by lateral mechanical variability, not by insufficient bearing capacity or excessive load.

Most lunar foundation discussions still revolve around whether the regolith can “carry the weight.” That question is outdated. Apollo-era data already demonstrated that the lunar surface is generally competent under modest loads. The real risk for modern lunar systems, reactors, landing pads, precision robotics, autonomous construction, is not collapse, but misalignment.

Differential settlement is a silent failure mode. It does not announce itself through dramatic instability or obvious distress. Instead, it accumulates gradually, driven by subtle but persistent contrasts in stiffness beneath nominally flat terrain. On Earth, engineers manage this risk through stratigraphic continuity assumptions, conservative zoning, and extensive subsurface investigations. On the Moon, those assumptions do not hold.

Lunar regolith is not a laterally uniform deposit. It is a mechanically discontinuous medium shaped by billions of years of impact gardening, ejecta emplacement, seismic shaking, and regolith maturation. Over distances of meters, not kilometers, the subsurface can transition between zones with fundamentally different stress histories and fabric. These transitions are invisible to orbital imagery and irrelevant to bearing capacity checks, yet decisive for settlement behavior.

This is where the OCR* framework becomes operationally relevant. OCR*, a lunar-adapted overconsolidation ratio analog, captures the mechanical memory of the regolith, integrating impact compaction, ejecta loading, and excavation history into a single stress-history proxy. Crucially, OCR* is not a depth-averaged scalar. It is a spatial field property with lateral gradients that directly control stiffness, compressibility, and time-dependent deformation.

When a foundation, landing pad, or reactor base spans zones with contrasting OCR* values, the governing response is no longer load magnitude, it is mechanical incompatibility. Even under identical loading, one portion of the foundation settles elastically while another undergoes delayed compression. The structure responds not as a rigid body, but as a system forced to accommodate uneven ground response through rotation, bending, or internal stress redistribution.

Apollo surface experiments already hinted at this behavior. Tilt and settlement responses varied significantly between sites that were visually indistinguishable and only kilometers apart. These differences cannot be explained by slope, load, or surface texture alone. They are consistent with lateral variability in regolith stiffness and stress history, exactly what OCR* is designed to represent.

As Artemis planning advances toward permanent assets with tight alignment tolerances and long operational lifetimes, this distinction matters. The next lunar infrastructure failure is unlikely to be a bearing failure. It is far more likely to be a precision failure, a reactor drifting out of alignment, a landing pad responding asymmetrically to plume loads, or an autonomous system encountering unanticipated resistance due to abrupt mechanical transitions beneath the surface.

This article reframes lunar foundation risk around that reality. It argues that differential settlement driven by OCR* contrast is the dominant geotechnical hazard for high-precision lunar infrastructure, and that managing this risk requires spatial characterization and homogenization strategies, not stronger foundations or heavier margins.

SpaceGeotech advances this discussion not as speculation, but as applied geomechanics, grounded in Apollo data, soil mechanics principles, and first-order physics relevant to mission architects, system engineers, and construction planners operating beyond Earth.

The Hidden Hazard Beneath Flat Terrain

Flat terrain on the Moon is routinely interpreted as mechanically benign. This assumption is embedded, often implicitly, in site selection workflows, landing analyses, and early foundation concepts. It is also wrong.

Apollo surface operations demonstrated that visually flat does not mean mechanically uniform. Post-installation responses, tilt, embedment, and time-dependent adjustment, varied substantially between sites that shared similar slopes, surface textures, and apparent soil conditions. In several cases, installations experienced markedly different settlement behavior despite comparable loads and geometries. These differences emerged not during emplacement, but over time, as the regolith responded to sustained stress.

From a geotechnical standpoint, this behavior is not anomalous. It is characteristic of ground systems where lateral stiffness contrasts dominate response. On Earth, such contrasts arise from interbedded soils, relic desiccation layers, or partially eroded deposits. On the Moon, they arise from a different but equally powerful set of processes: localized ejecta blankets, buried blocks, impact-induced densification, and variable regolith maturation depths.

The key point is that these features are laterally discontinuous at the meter scale. A foundation footprint can easily straddle zones with different compaction states and stress histories. When that happens, the governing deformation mode is not uniform settlement, but differential settlement driven by incompatible stiffness response.

This mechanism is largely invisible to traditional lunar site screening. Orbital imagery cannot resolve it. Slope maps do not capture it. Bearing capacity checks do not interrogate it. Yet once a structure is emplaced, the ground “decides” how the load is shared, and it does so according to local stiffness, not average strength.

Apollo-era soil mechanics investigations already documented strong local variability in density, penetration resistance, and inferred modulus over short distances. Footprint depths, rover track behavior, and penetrometer responses showed that regolith properties could change abruptly within a single work area. These observations were treated as operational curiosities at the time. For long-lived, precision infrastructure, they are design drivers.

Differential settlement does not require weak soil. It requires contrast. A stiff zone adjacent to a more compressible one will attract load unevenly, forcing the structure above to rotate or bend in order to maintain compatibility. Over time, even millimeter-scale differential movements can exceed alignment tolerances for systems such as reactors, radiators, landing pads, and autonomous construction platforms.

The hazard, therefore, is not instability. It is gradual loss of geometric control. Because the surface appears flat and competent, the risk is easy to underestimate, and easy to miss until correction is no longer possible.

This is the failure mode that lunar engineering must confront directly: not collapse, not bearing failure, but settlement mismatch rooted in lateral mechanical heterogeneity.

OCR* as the Spatial Variability Metric

The primary limitation of current lunar geotechnical thinking is not a lack of data, but the absence of a mechanics-based variable capable of translating observed heterogeneity into predictable structural response. OCR* fills that gap.

OCR* is not a surrogate for density, nor a rebranded strength index. It is a stress-history proxy adapted to lunar conditions, capturing the cumulative mechanical effects of impact loading, ejecta burial, seismic shaking, and regolith gardening. These processes do not act uniformly with depth or laterally. As a result, OCR* must be treated not as a single value beneath a site, but as a spatially variable field property.

This distinction matters because settlement is governed primarily by stiffness and compressibility, not ultimate strength. Small changes in OCR* translate nonlinearly into constrained modulus and shear stiffness. When OCR* varies laterally across a foundation footprint, the ground response becomes incompatible, even under uniform loading.

Consider a modest foundation footprint, on the order of 5 m × 5 m, spanning a transition between two regolith zones. One portion overlies material with an OCR* near unity, reflecting relatively recent disturbance or limited overburden history. An adjacent portion rests on regolith with a higher OCR*, reflecting impact densification or prolonged burial beneath ejecta. The applied load is the same. The deformation response is not.

The lower-OCR* zone accommodates load through greater compressive strain, while the higher-OCR* zone responds more elastically. The structure bridging these zones is forced to absorb the differential through rotation or internal stress redistribution. No bearing capacity criterion flags this condition. No slope threshold captures it. Yet the resulting bending moments and long-term tilts can exceed allowable limits for precision systems.

This is why OCR* must be interpreted laterally, not just vertically. Depth profiles alone are insufficient. What controls performance is the gradient of OCR* across the loaded area. Where that gradient is steep, differential settlement becomes the governing response, even if both zones are individually “competent.”

Apollo surface measurements implicitly revealed this behavior. Variability in footprint penetration, rover trafficability, and penetrometer resistance over meter-scale distances indicates abrupt changes in regolith stiffness and stress history. These observations align with a regolith fabric composed of mechanically discrete patches rather than continuous layers.

By framing OCR* as a spatial metric, the problem becomes tractable. Lateral OCR* variance can be mapped, compared, and filtered against system tolerances. Zones of mechanical compatibility can be distinguished from zones of latent mismatch. This moves lunar site evaluation from descriptive geology to predictive geomechanics.

The implication is direct: foundation performance on the Moon is controlled less by how strong the ground is, and more by how consistent it is. OCR* provides the first practical means of quantifying that consistency in a way that is physically grounded and operationally relevant.

Consequences for Critical Lunar Systems

Differential settlement driven by OCR* contrast is not a theoretical inconvenience. It is a system-level risk with direct implications for the performance, longevity, and safety of critical lunar assets. As infrastructure shifts from short-duration deployments to long-life, high-precision systems, tolerance to ground-induced misalignment becomes a governing design constraint.

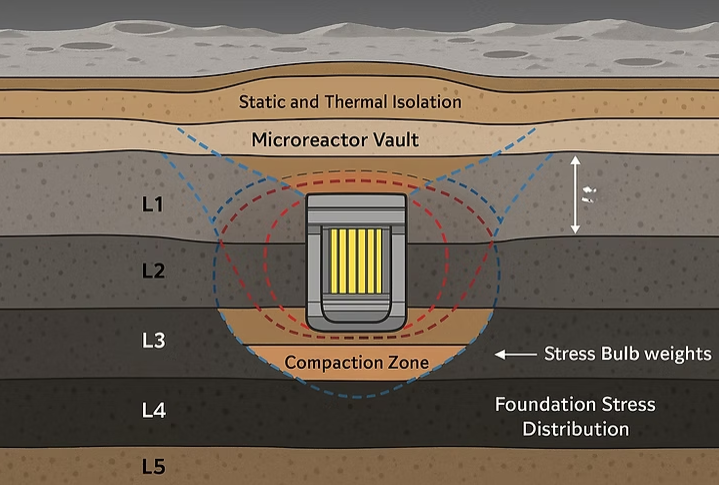

Fission Surface Power Systems

Surface reactors and associated thermal management hardware impose some of the strictest alignment requirements of any lunar asset. Radiator panels, heat pipes, and shielding geometries are sensitive to small rotations accumulated over time. Even millimeter-scale differential settlement across a foundation can translate into tilt that degrades thermal efficiency, introduces structural stresses, or violates operational envelopes.

The critical point is that these systems are not threatened by bearing failure. They are threatened by progressive, uneven deformation beneath a footprint that spans mechanically incompatible regolith. Once emplaced, correction options are limited. The failure mode is not abrupt, but cumulative, and therefore easy to underestimate during early design.

Landing Pads and Repeated Touchdown Zones

Landing pads are often treated as load-spreading elements designed to reduce bearing pressure and mitigate erosion. This framing misses a more subtle risk. If a pad or prepared surface spans zones with different OCR* values, the response to landing loads and plume-induced stress redistribution will be asymmetric.

Uneven settlement can alter load paths through landing legs, increase local contact stresses, and amplify plume–surface interaction on one side of the pad. Over repeated landings, this asymmetry compounds, increasing maintenance demands and reducing operational reliability. A pad that is strong but mechanically inconsistent is not a stable platform, it is a source of progressive degradation.

Autonomous Grading and Surface Preparation Systems

Robotic construction systems implicitly assume mechanical continuity. Excavation resistance, tool penetration, and traction models are typically parameterized using averaged regolith properties. Abrupt OCR* transitions violate those assumptions.

When autonomous systems encounter localized zones of higher compaction or stress history, the result is tool stall, over-excavation, or loss of grade control. These are not software problems; they are geotechnical surprises. Without prior identification of OCR* variability, autonomy is forced to react rather than plan.

Precision Instrumentation and Surface Networks

Scientific instruments, communication arrays, and alignment-sensitive platforms depend on geometric stability more than structural strength. Differential settlement introduces drift that cannot be calibrated out once it exceeds design tolerances. For networks spanning multiple foundations, inconsistent ground response becomes a source of relative motion that undermines system coherence.

Across all these cases, the pattern is the same. The dominant hazard is not insufficient capacity, but incompatible deformation. Systems fail not because the ground cannot support them, but because it does not respond uniformly beneath them.

Recognizing this shifts the engineering question. The issue is no longer “Can the regolith carry the load?” It is “Will the regolith respond consistently across the footprint for the life of the system?” That question cannot be answered without explicitly accounting for OCR* contrast.

A Geotechnical Protocol for Site Homogenization

If differential settlement is driven by OCR* contrast, mitigation cannot rely on stronger foundations or higher safety factors. The solution is mechanical compatibility, achieved by identifying and managing lateral variability before emplacement. This requires a shift from point-based characterization to footprint-scale homogenization.

From Capacity Checks to Compatibility Screening

Traditional geotechnical workflows emphasize minimum bearing capacity and average properties. For lunar infrastructure, this approach is insufficient. What matters is not whether each point beneath a foundation is “acceptable,” but whether the response across the entire footprint is consistent.

To operationalize this concept, SpaceGeotech proposes a Settlement Uniformity Index (SUI), a first-order metric derived from the spatial variance of OCR* over the loaded area. SUI is not a strength index. It is a compatibility filter designed to flag sites where lateral stiffness gradients are likely to dominate deformation response.

Conceptually, SUI evaluates the statistical dispersion of OCR* values sampled at a resolution comparable to the foundation footprint. High dispersion indicates a high probability of differential settlement, regardless of average strength. Low dispersion indicates a mechanically coherent zone suitable for precision assets.

Resolution Matters

Footprint-scale effects demand meter-scale characterization, not decameter averages. For high-precision systems, OCR* mapping should be performed at approximately 1 m spacing using rover-mounted penetrometers, thermal probes, or hybrid mechanical–thermal sensing tools. The objective is to capture abrupt transitions associated with ejecta lenses, buried blocks, and compaction discontinuities.

For critical infrastructure, target zones should exhibit low OCR* variance, not necessarily high OCR*. A mechanically uniform site with moderate OCR* is preferable to a stronger but heterogeneous one.

Homogenization, Not Reinforcement

Where OCR* gradients cannot be avoided, mitigation should focus on smoothing transitions, not simply strengthening weak spots. Localized compaction, sintering, or surface reworking can be used selectively to reduce stiffness contrasts across the footprint. This approach mirrors terrestrial practices for sensitive foundations, where differential settlement control takes precedence over peak capacity.

The design objective is explicit: minimize OCR* gradients beneath the foundation. Once compatibility is achieved, conventional structural design methods regain validity.

Why This Protocol Is Practical

This protocol does not require exhaustive subsurface exploration. It requires targeted, physics-informed screening aligned with system tolerances. It is deployable using near-term robotic assets and integrates naturally into pre-emplacement site preparation workflows.

Most importantly, it addresses the failure mode that matters. By controlling spatial variability rather than chasing worst-case strength, lunar engineers can reduce latent risk early, when mitigation is still feasible and inexpensive.

Why This Matters for Artemis - Now

Artemis is crossing a threshold. The program is moving beyond reconnaissance and short-duration sorties into infrastructure definition: surface power systems, prepared landing zones, logistics hubs, and semi-permanent installations with service lives measured in years, not hours.

At this stage, geotechnical risk no longer expresses itself as uncertainty, it expresses itself as locked-in assumptions.

Site selection decisions are being made today using criteria dominated by illumination, slope, thermal environment, and access to volatiles. These are necessary filters, but they are not sufficient for infrastructure that must remain aligned, serviceable, and interoperable over long durations. Once a site is selected and interfaces are frozen, correcting ground-related misalignment becomes expensive, disruptive, or impossible.

Differential settlement driven by OCR* contrast is precisely the type of risk that does not appear in early design reviews yet governs long-term performance. It does not violate bearing capacity. It does not trigger obvious red flags during emplacement. It manifests later, after assets are deployed, interconnected, and operationally coupled.

This timing matters. Artemis surface systems are being designed with tight tolerances and limited adjustment capability. Power distribution, thermal rejection, landing interfaces, and robotic operations all assume geometric stability that the lunar ground does not automatically provide. Ignoring lateral mechanical variability today transfers risk downstream, where margins are thinner and corrective options are fewer.

The value of addressing this now is leverage. Early identification of mechanically coherent zones, or early investment in footprint-scale homogenization, costs little compared to retrofitting alignment solutions into deployed hardware. Screening for OCR* consistency upstream enables smarter site zoning, clearer interface requirements, and more realistic performance expectations.

In short, Artemis does not need stronger foundations. It needs better ground compatibility decisions, made earlier.

This is the moment when lunar geotechnical engineering must evolve from descriptive characterization to performance-based site qualification. The missions being planned now will define the operational baseline for decades. The ground beneath them will decide whether that baseline is stable or quietly drifting out of tolerance.

Closing Insights and Implications for Artemis-Era Infrastructure

Lunar infrastructure will not fail the way early mission planners once feared. It will not disappear into dust, nor will it collapse under its own weight. The more credible risk is subtler and more consequential: loss of alignment driven by invisible mechanical contrasts beneath an apparently flawless surface.

On Earth, geotechnical design has long recognized that uniform strength does not guarantee uniform performance. Differential settlement governs the behavior of bridges, reactors, precision facilities, and deep foundations, not because soils are weak, but because they respond differently to the same load. The Moon is no exception. In fact, its regolith history makes lateral incompatibility more likely, not less.

The prevailing lunar engineering narrative still treats the ground as a vertically layered, laterally continuous medium. That simplification is increasingly misaligned with the needs of Artemis-era infrastructure. As systems demand tighter tolerances and longer service lives, the cost of ignoring mechanical contrast rises sharply.

The OCR* framework reframes the problem in terms that matter for design and operations. It shifts attention from average properties to spatial consistency, from capacity to compatibility, and from visible hazards to latent ones. This is not an academic distinction. It determines whether a reactor remains aligned, whether a landing pad degrades symmetrically, and whether autonomous construction systems operate predictably or continuously adapt to surprise.

The engineering implication is direct. Lunar sites should not be ranked solely by illumination, slope, or regolith thickness. They must also be screened for mechanical coherence at the scale of the intended footprint. Where coherence is absent, homogenization must precede emplacement. Where it is present, design margins can be used efficiently rather than defensively.

This is the next step in lunar ground engineering: acknowledging that the Moon does not punish us with collapse, but with inconsistency. Designing for that reality, explicitly and early, is how lunar infrastructure moves from demonstration to permanence.

SpaceGeotech advances this perspective as a platform for serious engineering dialogue, applied research, and collaboration. As lunar construction transitions from concept to commitment, geomechanics must evolve from descriptive characterization to performance-based ground compatibility assessment. OCR* is one step in that direction, and differential settlement is the failure mode it makes visible, before it becomes irreversible.

Roberto De Moraes

Author | SpaceGeotech Founder

Comments