When Engineering Quietly Becomes Geopolitics

- Roberto Moraes

- 6 days ago

- 11 min read

The Moon has entered its infrastructure phase.

For decades, lunar activity was framed as exploration. That framing no longer fits. Programs are now converging on specific terrain with the intent to place permanent assets: landing pads, power systems, communications infrastructure, and habitable structures. Once infrastructure touches ground, the nature of competition changes.

This is no longer about who arrives first. It is about who defines the ground conditions that everyone else must work around.

On Earth, this transition is well understood. Ports, tunnels, energy corridors, and transport hubs do not merely support economic activity; they structure it. Early infrastructure decisions constrain later entrants through geometry, access, load limits, and exclusion zones. The Moon is following the same logic, compressed into a far shorter timeframe and applied to a far more constrained physical environment.

Nowhere is this more evident than at the lunar South Pole.

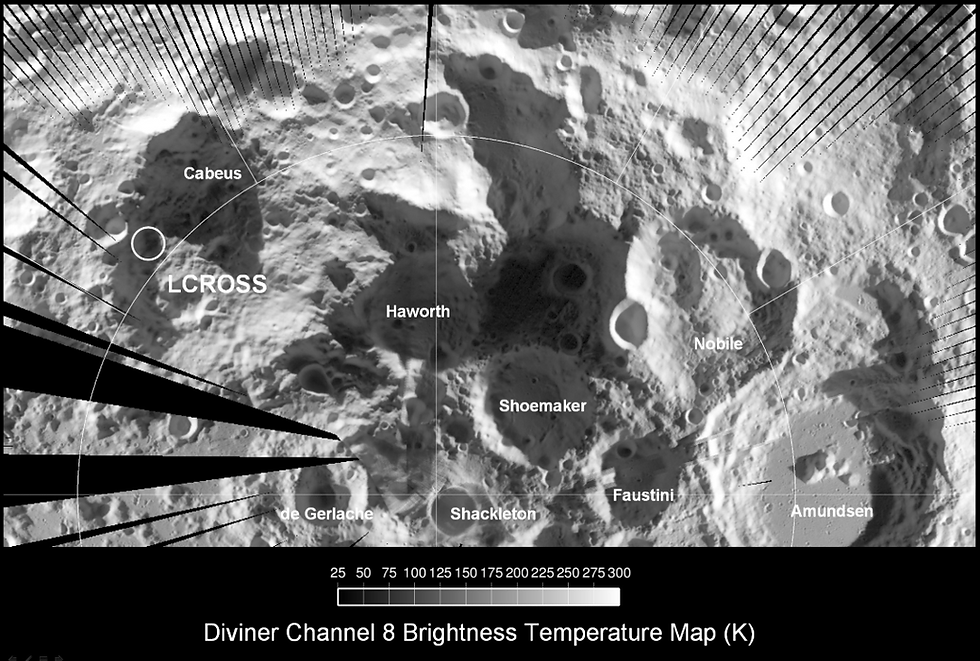

The South Pole is not valuable because of ideology or treaties. It is valuable because constructible terrain is scarce. Continuous illumination zones are narrow. Slopes transition abruptly. Regolith thickness, thermal regimes, and plume interaction envelopes vary over short distances. In practical terms, there are only a limited number of locations where infrastructure can be emplaced with acceptable risk.

This is where engineering quietly becomes strategy.

Much of the current discussion focuses on material characterization: regolith type, grain size, maturity, volatile content. These are necessary inputs, but they are not decision criteria. Knowing what the ground is made of does not determine whether a site can host infrastructure, support expansion, or coexist with neighboring systems.

Construction decisions are governed by a different question: can this ground be built on without compromising everything around it?

That question is captured not by material classification, but by constructability.

A Construction Suitability Index (CSI) integrates factors that material frameworks do not: slope, illumination continuity, bearing behavior, thermal cycling, excavation disturbance, and plume interaction. CSI does not describe the ground in isolation. It describes how the ground behaves once infrastructure is introduced.

This distinction matters because CSI is spatial and irreversible. Once a landing pad is stabilized, once regolith is sintered, once exclusion envelopes are established, the surrounding ground is no longer neutral. Future designs are constrained, access paths are fixed, and certain options are eliminated entirely.

At that point, competition is no longer managed through policy language. It is enforced by physics.

This article examines how constructability, rather than regolith classification alone, is becoming the de facto mechanism through which territory, access, and opportunity are structured on the Moon. It does not argue for or against cooperation. It explains why, without shared engineering assumptions, cooperation becomes mechanically unworkable.

Why Lunar Regolith Classification (LRC) Alone Fails as a Strategic Metric

Lunar Regolith Classification (LRC) is a material framework. It describes composition, grain size distribution, maturity, and in some cases inferred resource potential. That information is necessary, but it is not decisive. When LRC is used as a proxy for site viability, it produces conclusions that are operationally incomplete and, in competitive environments, strategically misleading.

The failure is not scientific. It is contextual.

LRC answers a static question: what is the ground made of?

Infrastructure decisions hinge on a dynamic one: what happens to the ground once we build on it?

This distinction is routinely respected in terrestrial projects. No major tunnel, port, dam, or power plant is approved on lithology alone. Rock type does not determine feasibility. Behavior under load, disturbance, and interaction does. On the Moon, that behavioral layer is often skipped, not because it is unimportant, but because it is harder to quantify with remote data.

As a result, LRC has been elevated beyond its proper role.

LRC remains essential for understanding material and resources.

My point is that once infrastructure is introduced, constructability, not classification, determines who can operate and expand.

Material Quality Does Not Equal Constructability

High-quality regolith, as defined by LRC, can be operationally marginal. Mature regolith may be resource-rich, auger-compatible, and mechanically interlocked at the particle scale, yet still be unsuitable for infrastructure due to slope, thermal cycling, illumination instability, or plume interaction constraints.

Conversely, lower-grade or less mature regolith can be highly constructible if it sits within favorable geometry and environmental envelopes.

This inversion is unintuitive but fundamental. Constructability is governed by system-level constraints, not material descriptors.

When LRC is treated as a strategic metric, it biases decision-making toward resource narratives rather than infrastructure realities. It encourages site selection based on what can be extracted rather than what can be supported. In a competitive environment, that bias matters.

LRC Has Limited Spatial Resolution for Infrastructure Decisions

LRC maps tend to be laterally extensive. Regolith types change gradually across kilometers. Infrastructure constraints do not. In other words, Lunar Regolith Classification operates at regional scale. Regolith units change gradually over kilometers. Infrastructure constraints do not.

At the lunar South Pole, the difference between viable and non-viable construction zones can occur over tens of meters due to:

slope breaks,

illumination shadows,

thermal gradients,

subsurface transitions,

plume interference envelopes.

LRC does not resolve them by design. CSI does. These boundaries are not material-driven. They are geometry- and interaction-driven.

Strategic outcomes on the Moon will not be determined by access to a regolith unit, but by occupation of the narrow zones where infrastructure can exist without destabilizing itself or its neighbors.

LRC Is Non-Exclusive by Nature

Material classification is inherently shareable. Multiple actors can extract value from the same regolith type without direct interference. Constructability is not.

Once infrastructure is placed, the ground state changes. Stabilization, compaction, sintering, excavation, and shielding introduce exclusion effects that propagate outward. These effects are not captured by LRC and cannot be mitigated by material abundance elsewhere.

This is the strategic blind spot.

Using LRC alone implies that access remains open as long as material exists. In reality, access closes when constructable ground is consumed or conditioned to serve a specific layout.

In competitive terrestrial projects, strategic ground decisions are always based on behavior:

settlement envelopes,

influence zones,

vibration limits,

exclusion radii.

The Moon is no different. It is more constrained.

CSI introduces these behavioral dimensions explicitly. It integrates material properties with geometry, environment, and interaction. It recognizes that construction is not a local act but a spatially coupled one.

LRC remains essential, but only as an input. Treated as a decision metric, it obscures the mechanisms through which early infrastructure decisions shape future access.

CSI Reframes Site Selection as Option Control

Once infrastructure becomes the objective, site selection stops being an exercise in preference and becomes an exercise in constraint management. This is where the Construction Suitability Index (CSI) fundamentally changes the logic of decision-making.

LRC supports exploration.

CSI governs commitment.

Where LRC highlights where material exists, CSI defines where future choices remain viable after construction begins. That distinction is not semantic. It is structural.

CSI Converts Ground Conditions into Strategic Constraints

CSI integrates variables that only matter once assets are emplaced: slope tolerances for landing systems, illumination continuity for power reliability, bearing behavior under repeated loading, thermal cycling effects on foundations and utilities, excavation disturbance, and plume interaction envelopes. These factors do not act independently. They compound.

A site with acceptable material properties but marginal geometry may support a rover or a drill campaign. It will not support a landing pad, a power hub, and a habitat without imposing exclusion zones that constrain everything around it. CSI captures this interaction explicitly.

The consequence is that CSI does not rank sites by attractiveness. It sorts them by irreversibility.

High-CSI ground preserves future options.

Low-CSI ground consumes them.

Scarcity Is Defined by Constructability, Not Resources

At the lunar South Pole, resource narratives dominate attention. Water ice, volatile retention, and regolith maturity are treated as primary drivers. From a construction standpoint, these are secondary.

The scarcest asset at the South Pole is not regolith. It is constructible geometry.

Continuous illumination zones are narrow. Slopes suitable for landing and surface operations are limited. Thermal regimes compatible with long-life infrastructure occupy thin bands. CSI collapses these constraints into a spatial reality: only a small fraction of the terrain can host infrastructure without triggering cascading restrictions.

This is why early infrastructure decisions matter more than later arrivals. The first actor to occupy high-CSI ground defines the configuration space available to everyone else.

CSI Makes Interference Predictable

Infrastructure does not coexist passively. Landing systems generate plumes. Power systems impose routing corridors. Excavation modifies regolith behavior. Stabilization alters thermal and mechanical response. Each of these effects extends beyond the footprint of the asset itself.

CSI incorporates these influence zones by design. It anticipates interference before it occurs, rather than reacting to it afterward. In doing so, it turns what is often treated as an operational issue into a planning variable.

This matters strategically because interference is the mechanism through which exclusion emerges without intent. No declaration is required. The ground simply becomes incompatible with alternative layouts.

From Site Selection to Layout Control

Traditional lunar site selection asks: Where should we land?

CSI reframes the question: Where can we build without foreclosing future configurations?

That reframing shifts the competitive axis. Control is no longer exercised by proximity to resources, but by control over layout-defining ground. Once power hubs, landing pads, and stabilized surfaces are fixed, future participants inherit a constrained design space.

This is not coordination failure. It is a physical consequence of construction.

CSI exposes that reality early, when choices still exist. Ignoring it does not preserve neutrality. It merely delays recognition until options have already been lost.

Strategic Control Emerges Without Strategic Language

Most policy frameworks assume that access, interoperability, and peaceful use can be preserved through coordination. That assumption holds only if infrastructure remains modular, reversible, and spatially unconstrained. Lunar infrastructure satisfies none of those conditions.

Landing pads impose plume exclusion zones.

Power systems demand protected corridors.

Stabilized ground alters adjacent regolith behavior.

These effects accumulate spatially. They do not require exclusivity by policy because exclusivity emerges mechanically. Once a high-CSI zone is conditioned to support one layout, alternative layouts become infeasible nearby. This is not governance by agreement. It is governance by ground state.

The space community has treated this as an operational inconvenience rather than a structural reality. That is a mistake.

Why “Peaceful Use” Does Not Address Constructability

Treaties and accords speak to intent, not interference. They regulate behavior, not bearing capacity. They assume that multiple actors can coexist if norms are respected. From an engineering standpoint, coexistence depends on compatibility of assumptions.

Two installations can both be peaceful and still be incompatible because:

their plume envelopes overlap,

their power routing conflicts,

their stabilization methods propagate thermal or mechanical effects,

their exclusion radii intersect.

None of these conflicts are political in origin. All of them are deterministic.

Ignoring this does not preserve cooperation. It guarantees friction once assets are fixed.

Early Builders Define the Rules Others Must Follow

In terrestrial infrastructure, early movers shape entire markets. Ports define shipping routes. Rail gauges determine supply chains. Grid topology constrains generation and storage. These outcomes are rarely debated as geopolitical when they occur. They are accepted as consequences of investment timing.

The Moon is no different, except that the margins are tighter and the reversibility is lower.

The first actors to occupy high-CSI ground do not need to assert control. Their engineering decisions define:

where future landings can occur,

how close others can approach,

which expansion paths remain viable.

Later participants inherit these constraints regardless of intent or capability.

This is the aspect that has been systematically overlooked by both science-driven and commercially optimistic narratives.

Why Industry Is Exposed, Whether It Acknowledges It or Not

Commercial actors often assume that competition on the Moon will be driven by launch cadence, payload mass, or ISRU efficiency. Those variables matter, but they are downstream.

The upstream variable is ground compatibility.

A company that designs infrastructure based on aggressive CSI assumptions may achieve early efficiency but impose exclusion effects that limit partnerships or regulatory acceptance later. A company that designs conservatively may preserve interoperability but sacrifice first-mover advantage.

These are strategic tradeoffs, yet they are rarely framed as such. They are discussed as technical optimizations, when in fact they determine who can coexist and who must work around whom.

The Silence Is the Risk

What makes this moment particularly unstable is not competition itself, but the lack of a shared engineering vocabulary for discussing it.

Without common definitions of constructability, interference, and exclusion, disputes will appear operational on the surface while being structural underneath. By the time they are recognized as strategic, the ground will already be altered.

Warning Signs the Community Is Ignoring

The signals are already visible. They are not speculative, and they do not require hostile intent. They emerge naturally when engineering decisions are made without acknowledging their strategic consequences. What is missing is not data, but recognition.

Convergence Without Coordination

Multiple programs are converging on the same narrow terrain at the lunar South Pole. This convergence is driven by illumination geometry and thermal stability, not policy alignment. Yet each program is developing its own assumptions for landing systems, ground stabilization, power routing, and operational buffers.

When independent design envelopes overlap in constrained terrain, incompatibility is not an exception. It is the default.

The warning sign is not that actors are competing. It is that they are designing as if they are not.

On Earth, standards follow accidents. In space, the consequences arrive faster and recovery options are fewer. The current pattern is to deploy infrastructure first and address interoperability later, under the assumption that engineering issues can be resolved operationally.

That assumption does not hold when:

exclusion zones are geometric,

ground modification is permanent,

and disturbance propagates beyond asset boundaries.

Once the ground is conditioned, there is no mechanism to reconcile incompatible assumptions without dismantling what already exists. That will not happen.

Treating Interference as a Local Problem

Plume effects, thermal disturbance, vibration, and dust transport are often discussed as localized issues, manageable through operational offsets or scheduling. At the South Pole, these effects scale differently.

Low gravity extends plume influence.

Thermal extremes amplify fatigue.

Dust remains mobile longer.

Local effects become area constraints. CSI captures this. Many planning frameworks do not.

The warning sign is the continued treatment of these effects as second-order, when they are first-order determinants of coexistence.

There is an implicit belief that transparency of data ensures compatibility of outcomes. This is false. Sharing regolith properties does not align design margins. Exchanging terrain maps does not harmonize exclusion envelopes.

Compatibility requires shared assumptions, not shared information.

Without agreement on what constitutes acceptable constructability, shared data only accelerates divergence.

Commercial Acceleration Without Ground Governance

The push toward rapid commercial deployment is understandable. Launch capacity has increased. Payload costs are falling. Timelines are compressing. What has not kept pace is a framework for managing ground interaction between independent actors.

This creates a structural imbalance. Speed becomes a means of shaping the environment before others arrive. Not through intent, but through precedence.

The warning sign is the absence of any serious discussion about how early construction decisions constrain later participation.

The Irreversibility Threshold

There is a point beyond which alignment is no longer possible. That point is reached not when treaties are violated, but when enough infrastructure is fixed that alternatives cannot be physically accommodated.

No one knows exactly where that threshold lies. What is clear is that it will be crossed quietly.

By the time it is acknowledged, the Moon will already be zoned by constructability, and the opportunity for deliberate coordination will have passed.

The Ground Will Decide Before Policy Does

Infrastructure programs are moving from intent to emplacement, and once construction begins, outcomes are governed by physics, not language. The community has treated regolith classification, resource mapping, and access principles as sufficient framing tools. They are not.

Material classification explains what exists.

Constructability determines what survives contact with infrastructure.

The strategic variable on the Moon is not who arrives first, nor who claims access. It is who fixes the ground state in the limited zones where construction is viable. Those decisions propagate outward through exclusion envelopes, interference zones, and irreversible layout constraints. They do not require enforcement. They enforce themselves.

This is not a warning about conflict. It is a statement about precedence.

Without shared constructability assumptions, cooperation degrades mechanically. Without explicit recognition of CSI as a governing metric, lunar development will fragment by default. By the time incompatibilities are visible, the ground will already be altered beyond negotiation.

The Moon does not need new treaties to become structured.

It needs only foundations.

Those who understand this will shape the next phase of lunar activity.

Those who do not will discover it after their options are gone.

That is the reality engineers already recognize on Earth.

The Moon simply removes the illusion of reversibility.

Author

Roberto de Moraes

Founder, SpaceGeotech

Lunar Geotechnics and Infrastructure Engineering

Comments