Helium-3 and the Limits of Speculation

- Roberto Moraes

- Nov 14, 2025

- 14 min read

The renewed attention around helium 3 has value. It draws companies, investors, and policy makers into a conversation that has long been dominated by abstract models and surface-level assumptions. For the first time in decades, the idea of a functioning cislunar economy is being discussed in practical terms rather than as a distant aspiration. This shift is healthy. It pushes the community toward questions of infrastructure, logistics, and industrial capability instead of speculation alone.

Yet one fact continues to be overlooked, and it is fundamental.

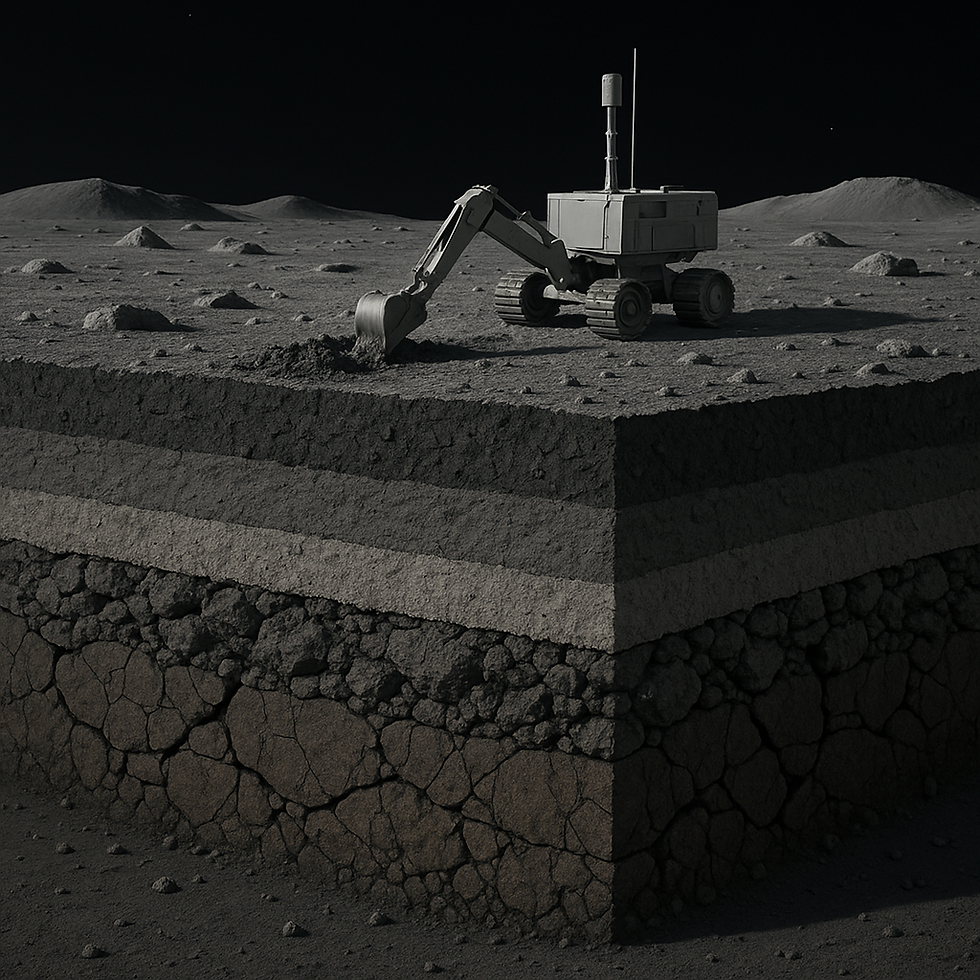

We have never drilled a single engineering grade borehole on the Moon. Not one. No project, civil or industrial, would be evaluated on Earth with such an absence of subsurface data. Still, we speak confidently about resource volumes, extraction concepts, and production rates as if the ground had already been characterized. The reality is that the ground remains unknown.

This gap is not academic. It defines the limits of any helium 3 discussion. Plans for surface harvesting, thermal desorption, or large-scale regolith collection assume that the near surface materials behave in a predictable and uniform way. They assume that the regolith is shallow, unconsolidated, and accessible. They assume that excavation forces are modest and that the mechanical stratigraphy does not change abruptly at depth. None of these assumptions have been verified. They cannot be verified from orbit. They require real geomechanics, real sampling, and real subsurface investigation.

From an engineering standpoint, the central constraint is not the presence or absence of helium 3. It is the absence of ground data. Without understanding the mechanical behavior of the lunar regolith, its consolidation state, its block content, and the transitions that occur within the first few meters, no extraction concept can be evaluated responsibly. Before the lunar economy becomes a question of production, it must become a question of subsurface knowledge.

This is the starting point. Everything else depends on it.

The narrative is built on models, not measurements

The popular storyline goes like this:

solar wind implants helium 3,

it accumulates in ilmenite rich mare basalts,

it exists in the top 3 meters,

and the surface “recharges’’ in about 100 years.

It sounds clean and compelling. But every one of these statements is unverified.

Apollo never drilled deep enough to characterize construction grade stratigraphy. We have no CPT, no DCP, no in situ stress path data, no OCR* mapping, and no stiffness or deformation profiles. The subsurface structure of the Moon remains unknown at the scale required for real engineering. The few core tubes we have are shallow, disturbed during recovery, and provide no continuous mechanical profile. They tell us almost nothing about how the ground behaves under excavation loads, repeated traffic, or thermal cycling.

Even the assumed depth of helium 3 is not based on measurements. It comes from optical maturity models, particle implantation physics, and general estimates of regolith turnover rates. These are useful in a scientific sense, but they do not replace direct testing. They provide no insight into excavation resistance, particle interlocking, hardpan development, or the transitions that occur between unconsolidated regolith, dense impact worked layers and block rich megaregolith.

Despite this, we continue to anchor trillion-dollar conversations in orbital inference rather than subsurface investigation. We reference concentration maps without knowing if the material is even mechanically accessible. We speak about harvesting without knowing if the first meter behaves like loose soil, dense gravel, or a cemented granular rock composite. We assume production without understanding the excavation energy required, the wear rate of tools, or the stability of disturbed ground.

This approach would not pass a preliminary review in any terrestrial mining project. It is the equivalent of planning a major extraction operation with only satellite images. There are no boreholes, no logs, no shear strength envelopes, no density profiles, and no constructability assessments. The ground exists only as a set of assumptions.

No engineer on Earth would accept that. The Moon should not be an exception.

The real barrier to helium 3 is the ground, not the economics

Let us assume, for a moment, that helium 3 exists in the upper few meters of the lunar surface. Let us also assume that the estimates of concentration are correct within an engineering order of magnitude. Even with those favorable assumptions, the central question is not the amount of helium present, but whether the ground that hosts it can actually be excavated at scale. The true constraint is mechanical, not economic. Before any discussion of production rates or commercial return, the feasibility of removing and processing the material must be established.

The common perception imagines the lunar surface as a uniform layer of loose dust, almost fluid in behavior, ready to be scooped, conveyed, heated, and processed with modest effort. This perception is incorrect. The Moon is not a powder bed. It is a mechanically complex granular rock composite shaped by billions of years of impacts, thermal cycling, and micrometeoroid bombardment. Its physical behavior has more in common with a compacted aggregate deposit, or even a weathered rock mass, than with a simple soil layer.

Several characteristics are significant. The particles are angular rather than rounded. There is no water, no chemical weathering, and no atmospheric transport to smooth their edges. This angularity leads to strong interlocking, which increases shear strength and excavation resistance. In many locations, the surface is underlain by impact worked layers that have been repeatedly compacted by seismic shaking and ejecta fallback. These layers behave as dense, interlocked granular strata rather than loose soil.

Hardpan development is another factor. The top few centimeters may be loose, but repeated micrometeoroid impacts and thermal cycles create zones of increased density and stiffness below. These zones may resist penetration by light equipment and may require significant excavation forces to break. The abrasiveness of the regolith is also extreme due to the sharpness and mineral composition of the grains. Wear rates will be far higher than on Earth and may dominate the operating costs of any excavation campaign.

Overburden on the Moon is reduced due to lower gravity, yet significant overconsolidation can still occur at depth. This is captured in the concept of OCR*, which reflects preloading from ancient impacts and long-term compaction processes. An overconsolidated material may appear shallow and accessible in theory but behave like a cemented mass when disturbed. The transition from fine grained regolith to block rich megaregolith is also unpredictable. Within the first meter or two, excavation may encounter large clasts, brecciated fragments, or partially cemented impact debris.

If the L3 to L4 zones are locked, cemented, or heavily overconsolidated, which is a reasonable expectation, the extraction of helium 3 is no longer a surface harvesting problem. It becomes a shallow mining operation. The distinction is important. Surface harvesting implies the movement of loose material. Shallow mining implies the fragmentation of a mechanically competent mass, the handling of coarse blocks, increased tool wear, higher excavation energy, and more complex stability considerations.

Shallow mining on the Moon has not been demonstrated. It has not been tested under real conditions, and the equipment required for it has not been validated in vacuum, extreme temperature cycling, or reduced gravity. No excavation performance curves exist. The mechanical behavior of the ground under repeated disturbance is unknown. The stability of cut faces, the formation of ruts or collapses, and the impact of excavation on adjacent infrastructure cannot yet be predicted with confidence.

In other words, if the ground behaves as current geomechanical reasoning suggests, helium 3 extraction will require a level of engineering capability that does not exist today. The barrier is not the value of the resource, nor the scale of the deposit. The barrier is the mechanical reality of the subsurface. Until that reality is understood and validated, helium 3 remains a geological idea constrained by an engineering unknown.

All the operational economics depend on parameters

Excavation energy, bucket penetration, wear rate, blower efficiency, reactor feed rates, all the operational economics depend on parameters we do not yet have:

no shear strength envelopes

no excavation performance curves

no real density–depth profiles

no compaction/trafficability evolution under cyclic loads

no large-scale disturbance tests

no thermal conductivity vs grain contact data at depth

This means any CAPEX or OPEX model publicized today is not grounded in engineering reality. A resource is only “economically viable” when we understand the geotechnical pathway to extract it.

Even if excavation challenges were modest, the industry still faces a deeper issue. We have no empirical basis for estimating the operational costs of large-scale regolith handling on the Moon. All current economic projections are built on assumptions about soil behavior, machine performance, and thermal processing that have never been validated under real lunar conditions. At present, the models are abstractions rather than engineering assessments.

Excavation energy is unknown. On Earth, the energy required to break and move material is defined through decades of field data, laboratory testing, and mining experience. The Moon offers none of this. The relationship between penetration resistance, shear behavior, particle interlocking, and excavation forces has never been measured. No performance envelope exists for any cutting tool or bucket operating in lunar vacuum, under reduced gravity, and across the temperature extremes of the lunar day.

Wear rates are another fundamental uncertainty. Lunar regolith is extremely abrasive due to its angular grains and the absence of chemical weathering. Tool steels, cutting edges, and mechanical joints will degrade far faster than terrestrial analogs predict. The only wear data we have comes from the Apollo suits and sample containers, and those observations indicate degradation that would be unacceptable in any industrial operation. Without quantified wear curves, maintenance intervals and equipment lifetime cannot be estimated, which makes cost modeling speculative.

Similarly, we have no real density depth profiles or compaction behavior for the first few meters of the surface. Terrestrial soils compact under moisture, overburden, and cyclic loading. Lunar regolith compacts under impact shaking, thermal cycling, and particle rearrangement in vacuum. The governing mechanisms are different. The response to disturbance is different. We cannot assume that density increases gradually or predictably with depth. We also cannot assume that repeated excavation and traffic will produce stable platforms for equipment operation. These factors influence productivity, mobility, and energy consumption.

Thermal properties introduce further complexity. Heating regolith to release helium 3 requires predictable thermal conductivity and heat transfer behavior. Yet thermal conductivity in lunar soils depends strongly on grain contact area and vacuum conditions. It increases with density, decreases with porosity, and changes with temperature. Without understanding the thermal gradients within the excavation horizon, any estimate of processing energy is provisional at best. Even the concept of “heating the regolith” assumes that regolith can be homogenized, conveyed, and processed as a consistent feedstock. That assumption still lacks mechanical evidence.

In terrestrial mining, cost models are built only after site investigation, laboratory testing, bench scale trials, and pilot operations. On the Moon, these stages have not occurred. The absence of in situ testing means that capital and operating cost predictions are derived from analogs that do not match lunar physics or lunar geology. As a result, the economic forecasts that circulate widely today are disconnected from the engineering realities that would govern actual operations.

Until excavation forces, wear rates, density variation, thermal behavior, and disturbance responses are measured directly on the lunar surface, the economics of helium 3 extraction cannot be evaluated responsibly. What may appear profitable on paper may prove infeasible in practice. Conversely, what appears difficult today may become possible with new methods, materials, or equipment. Only data can resolve this uncertainty.

The key point is straightforward. Without subsurface testing, cost models are assumptions. And assumptions are not a foundation for industrial planning.

The Moon lacks a geotechnical data architecture

This is the part the industry must confront:

We are trying to design landers, roads, power plants, ISRU reactors, pipelines, excavators, and mining systems before defining the subsurface.

This is backwards. On Earth, it would never be allowed.

Before mining comes mastery of:

regolith mechanics,

mechanical zoning (L1–L5),

OCR* mapping,

stratigraphy and transitions,

load-bearing behavior,

excavation performance envelopes.

Right now, that architecture does not exist.

Much of the current discussion assumes that the Moon can be treated as an open site where infrastructure can be placed wherever it is convenient. In reality, the surface conditions vary significantly from one location to another. Impact history, local stratigraphy, slope stability, particle size distribution, and the depth of block rich layers all influence the feasibility of construction. Without a geotechnical framework, these variations cannot be mapped, predicted, or managed. Designing excavation systems, landing pads, roads, or processing plants without that foundation is premature.

The same gap appears in mobility. Rovers and loaders are often presented as if they will operate on uniform terrain. But trafficability depends on density, stiffness, friction angle, and particle interlocking. These parameters change with depth and location. The surface may bear the load of a small rover, while the same ground may deform under the repeated cycles of an industrial vehicle. Rutting, collapse, or sinkage may occur unpredictably. None of this has been measured. The absence of such data limits our understanding of what machinery is viable and how operations would be sequenced.

The pursuit of helium 3 brings these weaknesses into clearer focus. It forces us to confront the reality that resource extraction, infrastructure development, and long term industrial activity all depend on a shared prerequisite: a reliable geotechnical database. No mining engineer, civil engineer, or construction manager would approve a project with zero ground truth. Yet the lunar program continues to advance on assumptions because there is no established process for collecting the data that would anchor decision making.

The result is a mismatch between ambition and readiness. We discuss mining before understanding excavation. We discuss processing before understanding feedstock behavior. We discuss construction before understanding bearing capacity. We discuss mobility before understanding subsurface variability. The helium 3 debate shows that the real bottleneck is not the resource, not the economics, and not the technology. It is the absence of basic ground knowledge.

Until that gap is closed, every proposal for lunar industry remains provisional. The future of the cislunar economy does not hinge on a single resource. It hinges on whether we can characterize the very ground we intend to work on.

What the sector must do next

If the helium 3 debate has made anything clear, it is that the development of lunar industry cannot move forward on assumptions. The next stage requires a deliberate shift toward methods that are standard in every other engineering domain. Before advancing to mining concepts, processing architectures, or economic forecasts, the sector must confront the absence of geotechnical knowledge and treat its acquisition as the first essential task.

This shift begins with reconnaissance, not construction. The lunar subsurface must be characterized with the same rigor applied to major terrestrial projects. Core sampling, mechanical penetration tests, seismic surveys, ground profiling, and targeted excavation trials must be carried out across representative regions. Only through these investigations can we establish the mechanical zoning of the regolith, understand the distribution of dense layers, identify block rich horizons, and determine the variability of the near surface deposits at scales relevant to industrial work.

A realistic Phase 0 roadmap looks like this:

Phase 1 - Reconnaissance Geomechanics

The first meaningful engineering step is the direct acquisition of subsurface data. This includes stratigraphy, density variation, block frequency, shear behavior, thermal response, and the degree of overconsolidation at depth. These measurements will not only clarify the feasibility of helium 3 extraction but will also define the requirements for landing pads, roads, foundations, shielding berms, reactor sites, and any structure intended to operate for more than a single mission. Without this information, every design remains provisional.

L1–L5 mechanical zoning

OCR* mapping tied to geomorphology

in-situ density + stiffness + shear metrics

Phase 2 - Subsurface Definition

The second step is to understand how the surface responds to disturbance. The Moon is a static environment until it is touched by a wheel, bucket, drill, or landing plume. Once disturbed, its behavior is unfamiliar. The absence of moisture, the angularity of particles, and the vacuum conditions lead to responses that defy terrestrial intuition. Ruts may deepen unexpectedly. Slopes may hold or collapse without warning. Thermal cycling can change density and stiffness within a single lunar day. These effects must be quantified in controlled field experiments before any large-scale activity can be undertaken safely.

hardpan depth

particle interlocking indices

excavation reaction forces

thermal/radiative property gradients

Phase 3 - Constructability & Production Modeling

The third step is to develop and test equipment designed for these conditions. On Earth, we evaluate machines by running them on real ground under expected loads. On the Moon, this has never been done. The designs currently proposed for excavation, hauling, processing, and construction are theoretical. They rely on assumptions about traction, shear strength, surface bearing, and wear rates that have not been validated. Only through systematic testing will it be possible to determine which machines are viable, which require redesign, and which concepts must be abandoned.

excavation energy curves

wear models

compaction and trafficability evolution

thermal desorption vs regolith fabric

Only after these steps can helium-3 economics be evaluated honestly.

The industry must also accept that excavation will drive the feasibility of any resource extraction effort. Performance tests must be conducted with real cutting tools, buckets, wheels, and tracks operating in lunar vacuum. These tests must measure penetration resistance, tool wear, thermal effects, and fragmentation behavior. The goal is not to prove a specific system. It is to understand the envelope of forces and energy required to move material efficiently and safely. Without this envelope, no mining system, however elegant in concept, can be evaluated for practicality.

A similar commitment is needed for mobility and construction. Roads, landing pads, reactors, and cabins all impose demands on the ground. The bearing resistance, settlement behavior, and long-term stability of constructed platforms must be studied. The effects of repeated thermal cycling, seismic shaking, and dust accumulation must be measured in the context of actual structures. These considerations are routine in terrestrial engineering yet remain absent in the lunar program. The transition from research to industry depends on filling this gap.

The sector must also establish a framework for risk management. Buried boulders, voids within brecciated layers, sudden changes in density, and the presence of cemented horizons pose real hazards to excavation and construction. Identifying and mapping these risks requires systematic investigation, not inference from orbital imagery. The safety of equipment and personnel demands that such uncertainties be reduced through field data and validated models.

Ultimately, the path forward is straightforward. The Moon must be treated as an engineering site. Before building on it, working on it, or extracting resources from it, the ground must be understood. Every industrial operation depends on this understanding. It determines feasibility, cost, safety, and long-term performance. The sector has reached a stage where progress will no longer be defined by new concepts, but by the acquisition of the data required to evaluate those concepts responsibly.

Conclusions

The renewed interest in helium 3 has served an unexpected purpose. It has revealed that the most valuable resource on the Moon is not an isotope. It is knowledge of the ground itself. We cannot claim to understand the feasibility of helium 3 extraction, or any other industrial activity, without first understanding the mechanical behavior of the material we intend to work with. Until we obtain that knowledge, the surface remains a scientific landscape rather than an engineering site.

Every major infrastructure project on Earth begins with the same sequence. First, we investigate the ground. Then, we characterize it. Only after that do we design and build. The Moon is no different. The absence of water, the reduced gravity, and the nature of impact generated deposits do not change the fundamental logic of engineering. They reinforce it. The more unfamiliar the environment, the more essential it becomes to measure it directly.

Helium 3 is often described as a gateway to a new energy economy. In reality, its most important contribution may be that it forces the space sector to confront the limits of its current knowledge. The Moon cannot support a mining industry, a construction sector, or a manufacturing base until the subsurface is understood with the same rigor that we apply on Earth. That understanding does not come from models. It comes from field work, data collection, and the disciplined interpretation of real measurements.

The path ahead is clear. Before missions are built around extraction, they must be built around investigation. Before machinery is designed for production, it must be tested for traction, cutting, and wear. Before economic forecasts are published, the mechanical parameters that govern cost must be known. Progress will not come from larger concepts or more ambitious timelines. It will come from the slow, methodical acquisition of geotechnical knowledge. Once that foundation is established, the Moon will shift from a theoretical frontier to a practical one.

The first step of lunar industry is therefore not mining. It is measurement. The first major achievement will not be extraction. It will be the first engineering grade characterization of the subsurface of another world. Only then can we speak about helium 3, or any other resource, with the confidence that comes from understanding the ground beneath our feet.

Thanks for your sound and objective essay on lunar He3 mining feasibility. I am in complete agreement.

I would like to add one point. The market for He3 is predominately as fuel for nuclear fusion. Wait a minute, when did humanity finally reduce-to-practice fusion power generation? I am totally in favor of fusion R&D, however it is far from practical with a long way to go to overcome technical obstacles. Hopefully, stellarators might get us there one day.

So what technically competent investor is going to make a play to produce fuel for a non-existent power generation technology?

Having spent 30 years designing, building, and operating the International Space Station, I’ve seen more than my share of hare-brained “business plans”…